– Vilma Lorena Parada for Supermarket Art Magazine 2025

The boundary between artistic expression and transgression is a delicate and timeless subject – one that has commanded attention ever since art became a vessel for humanity’s dialogue with life and the essence of being alive. To cross this boundary is to venture into realms of profound breakthroughs but also into potential disruptions of the established order. When art edges too close to political borders, history reveals a recurring pattern: in many nations, those who dare to cross are often met with silence imposed upon them and liberty stripped away. This raises an enduring question: where does the line of freedom of expression lie when art critiques authority and stirs tension among those who wield power and won’t tolerate dissent?

In 2017, I first encountered Frank Lahera O’Callaghan through the message:

”Hello, I’ve been having internet issues here and haven’t been able to complete my online application. Could you please give me an extension to upload the video and submit it?”

He was responding to a call for submissions to the Faenza Video Art Festival in Colombia. I thought, yes, of course you can have extra time. He ended up submitting his application by email with a much lighter version of his video, Cuestión de perspectiva (A Matter of Perspective). The work was later selected for screening at VAF 2018.

At the time I could not fully grasp the reality in which Frank created his art. Over the years as our collaboration deepened – culminating in the co-production of the festival’s second edition in Santiago de Cuba in 2019 – I began to understand. To bring the festival to Cuba we transported 11 hours of video screenings, one projector, and our collective determination. The logistical challenges began immediately: it took over two hours for customs to clear the projector despite having the necessary documentation. Once cleared we embarked on a 12-hour drive from Havana to Santiago, carrying not only equipment but also the hope of connecting with Cuban audiences.

In Santiago we encountered a vibrant yet constrained artistic community. During an intimate meeting in a room filled with books and literature, the atmosphere was charged with both apprehension and unspoken urgency. Conversations about art, revolution, and dissent unfolded in hushed tones. The question lingered in my mind: can one create a revolution from within a revolution?

This experience left an indelible impression. It underscored the immense challenges Cuban artists face in navigating the fine line between expression and repression. We flew back to Colombia and promised to keep working together.

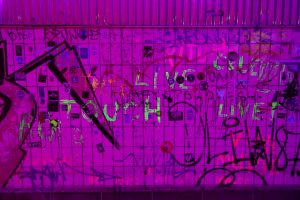

Frank Lahera O’Callaghan, ‘Noticias fuera de TV’ (News Outside of the TV), digital photography, 2023

Art and Resistance

I remember the occasion of the 14th Havana Biennial in 2021. We were having a meeting with Miler Lagos in his studio in Bogotá, Colombia. He mentioned he was going to participate with his piece Tic Tac, a time capsule made from pages of the Granma (Cuban newspaper), which highlighted how the newspaper had an incessant intention of bringing alive all the events that had happened during the revolution. I asked, “Have you made sure they’re okay with you using their communication medium in your piece and that they won’t take it as a critique?” There was a slight silence, and then we carried on with the conversation.

I later spoke to Frank and told him Miler had been invited. Frank explained that there had been major social unrest in Cuba. Protests had erupted in response to post-pandemic hardships and the implementation of Decree 349 – a law requiring artists to seek government approval for public and private work. Artists were infuriated and armed themselves with the strength to walk out into the streets, protesting not only the new law but also the prolonged and unbearable results of COVID-19: the lack of food, electricity, and basic supplies for the population.

Frank’s accounts of these events were harrowing: artists disappeared, were jailed, or had their work confiscated. It reminded me of historic events in Europe and Latin America, where art, artists, and intellectuals were declared enemies of the government. The Biennial, once a celebration of creativity, became a symbol of complicity in systemic oppression. Not long after artists began pulling out and it was clearly seen as a smokescreen distracting from the injustices endured by the Cuban people. Miler withdrew saying that participating would mean ignoring the unacceptable reality artists and people were facing. Freedom of speech should never be banned, he said. Amid this turmoil Frank continued to create. His defiance, though fraught with risk, reflected an unwavering passion for his craft.

Two Artists, Two Visions

Frank and Ernesto hail from Cuba, though from vastly different backgrounds and with contrasting artistic visions. Today they find themselves in Portugal, awaiting a decision on their application for political asylum.

Frank spent most of his life in Santiago de Cuba, where he earned degrees in Sociocultural Studies and Audiovisual Communication with a specialisation in directing. At 36, he has had over 35 exhibitions, more than 25 short films spanning fiction, documentary, and experimental genres, and several feature films. His art is a raw commentary on the tension between state censorship and the artist’s powerlessness in the face of persecution. It speaks of the suffocating lack of freedom to criticise a government through creative expression.

Ernesto, on the other hand, lived most of his life in Havana. A graduate in visual arts with a focus on painting, his work centers on vivid memories of his festive childhood, evoking imagination, magic, and the hope for a better future. With over 20 exhibitions and a history of impactful community work – developing art workshops for children in drawing, painting, and photography – his artistic journey has been one of fostering wonder and optimism. In November 2023, as I was preparing to invite Frank to participate in LA Art Stockholm, I received a message:

”Sorry, Lorena, the police came to my house yesterday to search for evidence linking me to the recent protests in Santiago. Amid everything, I couldn’t charge my phone. I’ll connect in a few minutes.”

When we spoke later, Frank explained they had found no evidence to justify arresting him, but the incident left him contemplating a move to Havana, where he hoped to create art with fewer restrictions. Despite the risks Frank continued creating and sharing his art on social media. I often wondered – if creating art jeopardised his freedom, how could he persist, and why did he risk sharing it publicly? I hesitated to ask, fearing my question might endanger him if his phone or accounts were monitored. He eventually moved to Havana and continued creating his work. I could see he was active through his posts on social media.

In April 2024, Frank shared that he had been accepted into an artist residency in Portugal. By September, his visa was approved, and he embarked on the journey with Ernesto. Two months later, they completed their residency at the UNESCO Center in Beja and are now awaiting a decision on their asylum request. During this time, Ernesto has remained true to his craft, painting scenes of animals and landscapes imbued with hope for a brighter future. Frank, in contrast, has delved into introspection; his new works reflect his personal transformation and reinvention.

Ernesto Sanchez Nuñez, ‘El sonido del silencio’ (The Sound of Silence), acrylic on canvas, 70 x 100 cm, 2024

The Fine Line

The fine line of art connects these two creators, bound by a shared experience of censorship and the longing for a future where they can express themselves freely. Along their journey they’ve encountered networks of individuals and artists who have helped them carve out a space where their voices can flourish – where they can explore the world beyond the confines of their past, and their creativity can reach new horizons.

The passion for art demanded sacrifices: family, language, cuisine, and the comfort of the known. For Frank and Ernesto, there is no return – only the road ahead guided by their art and the destinations it leads them to.

This fine line, once crossed, leaves no way back. For some it is the line between silence and expression, oppression and freedom, or darkness and light.